By Richard Schlesinger

On a dusty road leading out of the mountains, a hundred or so villagers form a caravan leading horse-drawn carts laden with their belongings. In the distance, the sound of artillery blasts, the acrid smell of gunpowder, the swirling black smoke of houses burning. A young mother in the caravan carries a child strapped to her back. She holds the reins of a mare heavy in foal.

The villagers are refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh, the horses a rare breed known as the Karabakh unique to the Caucasus region.

A sudden explosion nearby throws mother, child, horse and possessions to the ground. Amid the surrounding wails and confusion, blood from the mare’s wound turns the dusty road crimson. The young mother protects herself and her child behind the body of the dying mare as automatic weapons fire rings out all around them. The horse will not survive, though in shock, she foals.

In the ensuing calm, the young mother struggles to her feet, her child clutched tightly to her breast. The young foal too stands on its wobbly legs and turns its head toward the mountains where the refugees’ village burns.

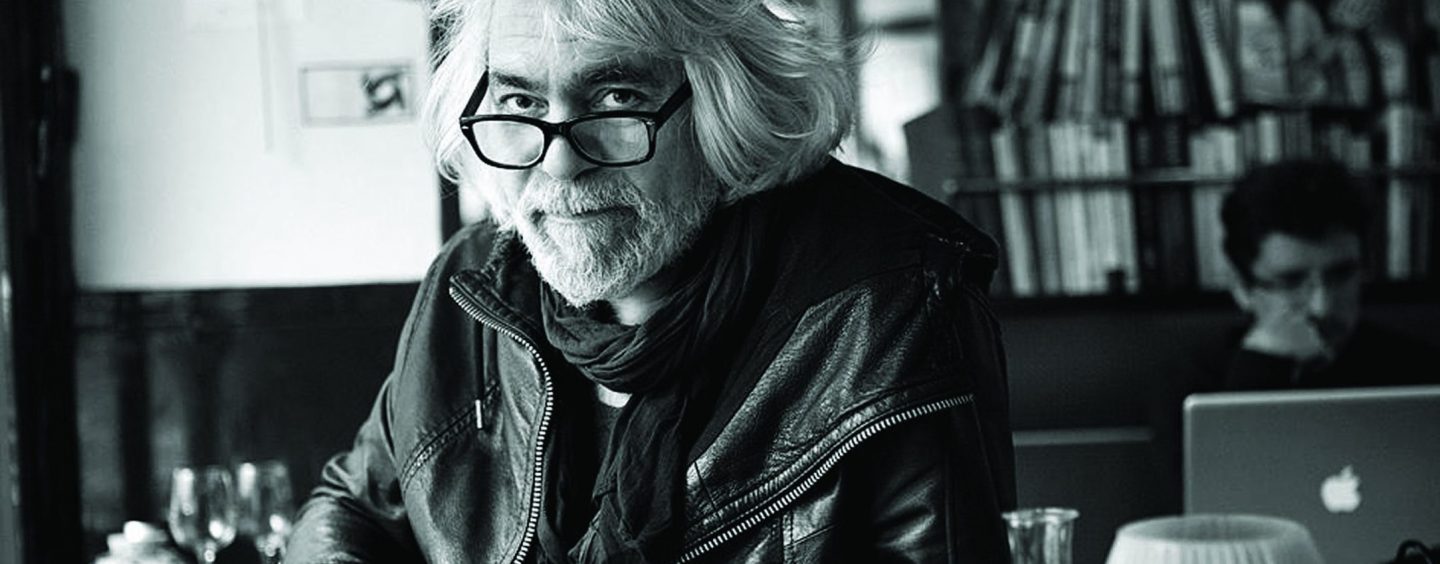

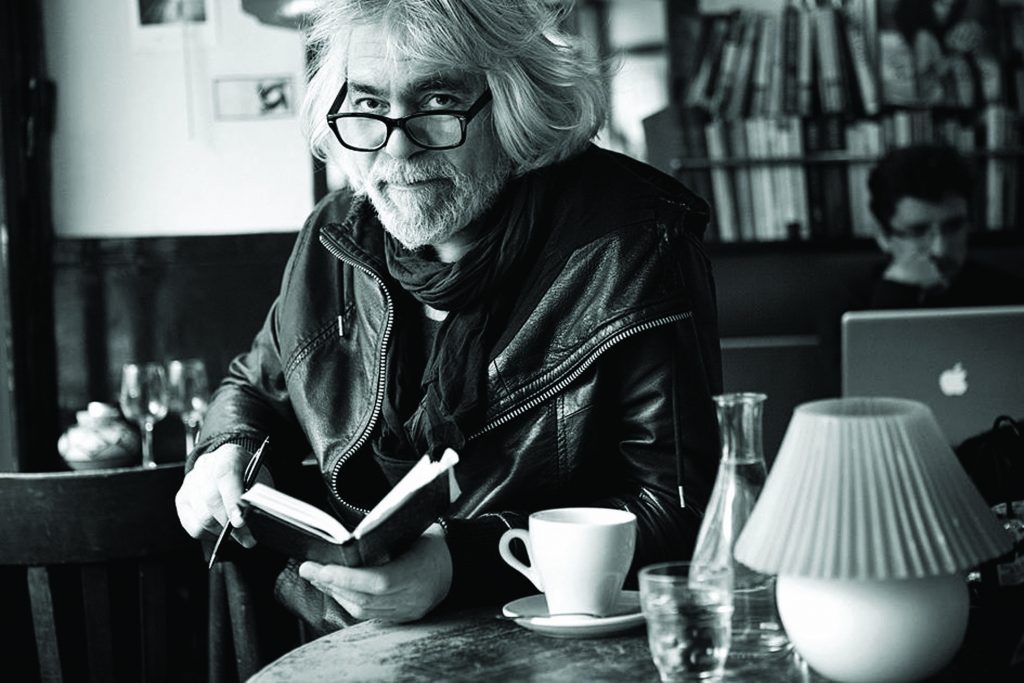

Film director Maxime Mardoukhaev has these images burned in his mind since he first returned to his own Azeri roots shortly after Azerbaijan became an independent nation. “You have to realize,” says Mardoukhaev, “I come from a country that no longer exists.”

Mardoukhaev was born in Moscow in what once was the Soviet Union. Not Russia. He is careful to point out the distinction.

“My parents were both immigrants. My father was born in Baku, my mother though Russian was born in Paris. My father is what people call today a Mountain Jew, from the villages of the high slopes of the Caucasus. My mother comes from a Russian aristocratic family. Theirs was the kind of union that could only happen in the USSR, a princess who married a peasant.”

Mardoukhaev’s mother is the granddaughter of the eminent theater director and acting guru Konstantin Stanislavski, and the great-granddaughter of one of the 19th century’s greatest writers, Count Leo Tolstoy. It was in this rarefied air of Russian cultural life that the young Maxime was raised for the first thirteen years of his life. His cosmopolitan Moscow education included piano, theater, opera, literature, everything you might expect from a family whose background formed the foundation of Soviet Russian culture of the 20th century.

Summers he spent with his father’s family in Baku, the diametrical opposite of his Moscow environment. An untold number of aunts, uncles and cousins frequently gathered around the great dining room table for birthday parties or family reunions, with loud conversation, music and dancing. “It was very folkloric.”

And then, quite suddenly in 1973, Mardoukhaev’s mother received permission to return to live in Paris. She, Maxime and his younger brother Kyril would be the first three Soviet citizens allowed to leave the USSR without renouncing their citizenship. Still, the young Mardoukhaev realized that, like a displaced person, he would be leaving behind him forever the familiar confines of Moscow and Baku.

The rift with his Soviet upbringing occurred at a very precise moment in his life. Even though he was now living in Paris, Mardoukhaev was enrolled at the Soviet Embassy school. All his fellow students were children of Soviet functionaries and diplomats, but he and his brother were classified as émigrés, a status never before applied to Soviet citizens. Like all Soviet youth of that time, Mardoukhaev was a member of the Pioneers, the Communist youth organization, recognizable by the red kerchief worn around the neck. When the authorities discovered that Mardoukhaev did not wear his Pioneer kerchief outside of school, they reprimanded him for his behavior and kicked him out.

His alienation was compounded when he entered a French lycee, where he was the first and only Soviet any French high schoolers had ever met. They thought he must be a spy.

During these years, Mardoukhaev began to show a lively interest in theater and the craft of acting. He enrolled in acting classes at one of Paris’ best known academies, the Cours Florent.

Upon completion of his high school diploma, Mardoukhaev was allowed to return to the Soviet Union. It is hard to imagine today just how rare this privilege was. People who left to live outside the USSR were defectors, they were not allowed to return. But Mardoukhaev remained a citizen. When he did go back in 1978 at the age of 18, excited to see his childhood friends again, he was surprised by their reaction to him. For them, as someone who turned his back on his own country, he could only be one thing, a traitor.

A spy, a traitor – young Mardoukhaev was neither. He was a free electron, unbound by the restrictions of a totalitarian state but still a part of it. He saw the limitations to travel freely throughout the world as a fundamental injustice. “I promised myself then and there that I would live my life as a world traveler, to see and experience as much of the world as I could and even to seek out a profession which would permit me that freedom.”

As a way of recapturing the familiar Soviet world he had missed while in France, he procured himself a 16mm camera and began filming everything he saw. He wanted to prove to his friends in Moscow that he knew his own country better than they did. Of course, he was followed by the KGB, and his films were confiscated and destroyed. But he had found his destiny. And so it was that, upon his return to France, he became a filmmaker, to travel the world and be a free thinker.

In subsequent years, Mardoukhaev had the good fortune to go to the United States to make films. It was an experience that opened his mind to world cinema. While shooting a documentary about the influence of his great-grandfather Stanislavski on the art of acting, he discovered that his heritage opened doors to a closed circle of Hollywood stars. Actors like Al Pacino, Robert de Niro, and Marlon Brando, received him to talk about their craft.

During the 1980’s the world began to change. Perestroika came to the USSR and the West took a renewed interest in what was known at the time as the Eastern Bloc. Mardoukhaev’s work in documentaries and journalism led him to join the Capa Agency, the most important television and press agency in Paris, where he ran their division devoted to the Soviet sphere of influence. During this period, he made his first film in Azerbaijan, covering the conflict with Armenia.

Mardoukhaev had always been fascinated by the Kremlin, not the symbol of power but the actual fortress itself, the day-to-day operations inside the walls. In 1991, he began filming his documentary “Kremlin”. At the time, he was the only documentary filmmaker who had ever been allowed inside to see the inner workings of the seat of Soviet power. During the course of filming, the Soviet Union collapsed. His was the only Western camera to capture the lowering of the Soviet flag and the raising of the new Russian flag at the fortress.

That same year, Mardoukhaev created his own company, Orient Express, to produce films with young emerging Russian directors who were cut loose by the swiftly crumbling Soviet system. He produced The Castle adapted from the Franz Kafka novel, the first feature film from renowned Russian director Alexei Balabanov (who went on to make the mega hit Brother).

Since that time, Mardoukhaev has gone on to direct more than 50 documentaries. Several have been in Azerbaijan, notably “Krasnaya Sloboda” about the Azeri Jewish community, “The Baku Operahouse, Replica of La Scala,” a film about Azerbaijani television, and three films which touch on the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia (“20 January”, “At the End of the Tracks”, “The Return”).

“At the End of the Tracks” tells the story of an entire city of displaced Karabakh refugees living in abandoned cattlecars in the trainyards of Imishly, near the Iranian border. These displaced persons, numbering 20,000 men women and children who escaped the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, found shelter in the derelict trains. In order to make this film, Mardoukhaev lived in the cattlecar city with the refugees for more than a month.

The film focuses primarily on the lives of children displaced by the war, surviving with their families and going to school in this unexpected environment. In so doing, it captures the real effects of immigration and displacement. In spite of the deprivation these children struggled with on a daily basis, Mardoukhaev says he was particularly impressed by their dignity and the strength of their belief in a better future.

One of Mardoukhaev’s unique specialties has been to return years later to the same characters he filmed previously as a way of discovering what has become of them. Fifteen years after the film “At the End of the Tracks”, Mardoukhaev returned to Azerbaijan to locate the cattlecar children. What he found astonished him.

Many of the children had grown up to start their own families, and thanks to a government program of relocation and housing, they were able to establish themselves throughout the country. They were no longer living in squalor, they had proper apartments or houses and had what to all appearances would be a happy life. But though they were extremely grateful to the Azerbaijani government for having given them the help they needed to succeed, they were not happy.

Almost all these young men and women, fathers and mothers, felt the overwhelming desire to return to their homeland. Their true home, they told him, is Nagorno-Karabakh. They wanted to go home.

For Mardoukhaev, who himself has always lived as a citizen of the world, this desire of an immigrant population to return to its homeland is a powerful statement. It is what is driving him now to devote himself to making a feature film about the Karabakh people, and the Karabakh horses.

It is said that the Karabakh horses always try to escape and return to the place of their origins, as if they know they’re a part of the Nagorno-Karabakh highlands, that their force, their pride and their spirit emanates from this land. When Queen Elizabeth II during the 1950’s received a gift from the Soviet Union of a young Karabakh stallion, she looked into its eyes and saw only sadness and longing. She graciously thanked the Soviet people for their generosity, but she chose to return the horse to his native land.

In Mardoukhaev’s story, the young boy and the horse grow up as displaced immigrants. They go on to race in and win championships around the world, in Paris, in London, in Dubai, and in the USA. But one day, while on hiatus after a series of victories in their exquisite stables in Baku, the horse escapes. Pulled by an irrepressible instinct, he takes off at a gallop toward the mountains of his ancestors and doesn’t stop until he gets there.

In France, this film project has already attracted the attention of an important French production company that works regularly with one of the major American studios. But above and beyond the creation of an international success with broad commercial appeal, Maxime Mardoukhaev – a French-Russian-Jewish Writer-Director from Azerbaijan – truly believes this film will express the unity and freedom of the Azeri Nation.

“The Karabakh horse is the true symbol of Azerbaijan, even more so than its silk, oil, and caviar. This unique breed represents courage, strength, pride, authenticity, beauty, and individuality. As such, it is the true flag bearer of its homeland.”