By Amir Ali Sardari Iravani

The Iravan Khanate, an independent state in the South Caucasus, emerged in 1748 and lasted until 1828. Initially a self-governing khanate, it came under the control of the Qajar dynasty by 1805. Strategically located and historically contested, Iravan served as a trade and cultural hub between Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. The region’s long history includes its founding as a center during the Safavid period, experiencing cycles of destruction and reconstruction as it changed hands between the Safavid and Ottoman Empires.

The city of Iravan (modern-day Yerevan, Armenia) was established as the capital of the Iravan Khanate. It was strategically important, located between the Ottoman Empire, Georgia, and Iran, and it sat at the crossroads of trade routes that linked the South Caucasus with other parts of Eurasia. This favorable geographic position made Iravan economically prosperous but also vulnerable to conflicts, as it was often a target for regional powers seeking control over its commercial routes and influence. Over centuries, Iravan developed into a culturally diverse hub, with a society shaped by a mosaic of religions, languages, and traditions. Western travelers of the era frequently described the cultural and religious tolerance within the khanate, particularly when compared to other regional cities.

After the death of Nadir Shah, the founder of the Afsharid dynasty, in 1747, Mir Mehdi Khan briefly ruled Iravan before being replaced by Azad Khan, an Afghan general. Soon after, Hasanali Khan, an Iravan native, was supported by locals to assume power in 1755, establishing a period of native leadership and relative stability. This era marked a fifty-year stretch of independence, during which Iravan’s rulers skillfully maintained a balance of power with neighboring states like Iran, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire to preserve autonomy. Hasanali Khan and his successors, especially Mahammad Khan, practiced astute diplomacy, leveraging rivalries between these powers to prevent Iravan from falling entirely under foreign control.

The Qajar dynasty, founded by Agha Mohammad Khan in 1789, soon rose to power in Iran, marking the beginning of heightened tensions for the Iravan Khanate. The Qajars were ethnically Turkic, with many of the Caucasus khans sharing similar backgrounds. However, the Iravan khans did not initially trust the Qajars, viewing them as new and unproven leaders. Agha Mohammad Khan ultimately invaded the Caucasus, capturing and detaining Mahammad Khan of Iravan but sparing his life. Despite this, the Iravan khans continued their diplomatic balancing act with Russia and the Qajars, maintaining a level of semi-autonomy until Mahammad Khan was exiled in 1805. Fath Ali Shah Qajar, Agha Mohammad Khan’s successor, attempted to consolidate control by appointing loyalists like Husseinqulu Khan from Qazvin to govern Iravan, a move that ultimately led to resentment and further unrest.

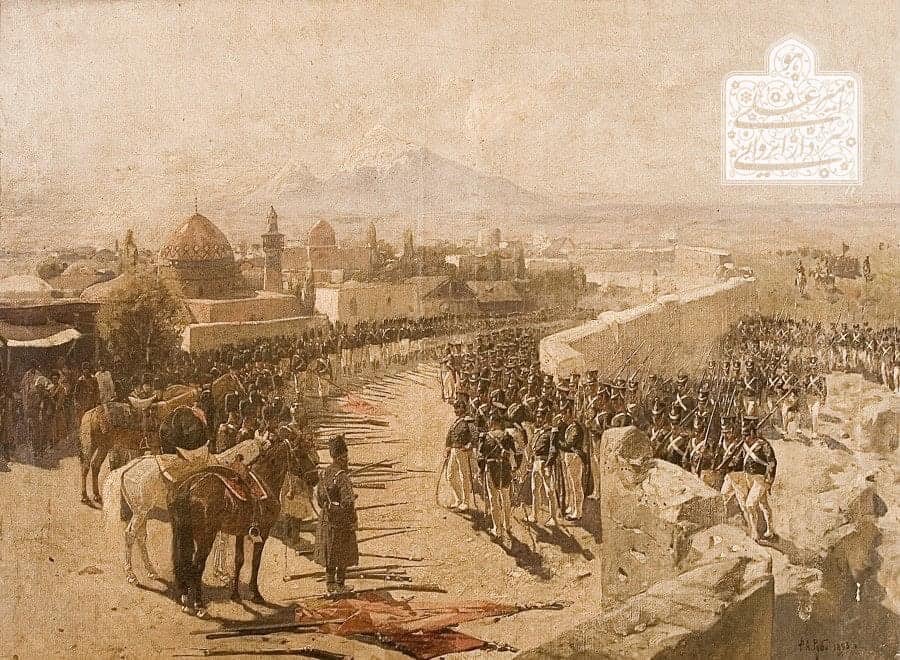

From 1805 to 1828, Iravan was formally under Qajar rule, though it retained some autonomy. However, Qajar interference, compounded by the khanate’s internal tensions, led to heavy losses for the Qajars in the Russo-Persian Wars. These conflicts culminated in the treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828), which ceded significant territories, including Iravan, to the Russian Empire. Following these treaties, Iravan’s history was increasingly documented by external powers, shaping the narrative in favor of Russian and later Armenian perspectives.

The Iravan Khanate’s heritage was deeply shaped by the Safavid Empire’s early influence, which saw Iravan’s strategic value and invested in its defense against the Ottomans. The Safavids appointed trusted generals to oversee the city’s fortifications, and its trade significance attracted diverse cultures, religions, and intellectual exchanges. During the khanate period, Iravan was known for its progressive approach to governance, fostering an environment conducive to trade and social tolerance. Schools and mosques became centers of learning, and some of the earliest efforts toward a modern educational system in the region were initiated in Iravan.

Iravan’s diverse religious and cultural landscape saw a mix of mosques, caravanserais, and other facilities for travelers and merchants, reinforcing its role as a cultural bridge between East and West. By the 18th century, Iravan had earned a reputation for religious tolerance, drawing admiration from Western travelers who documented the peaceful coexistence of various religious communities. The khanate’s leaders made efforts to integrate its Christian Armenian population, offering tax relief and protections, although external pressures from neighboring Christian states like Georgia and Russia occasionally stirred tensions.

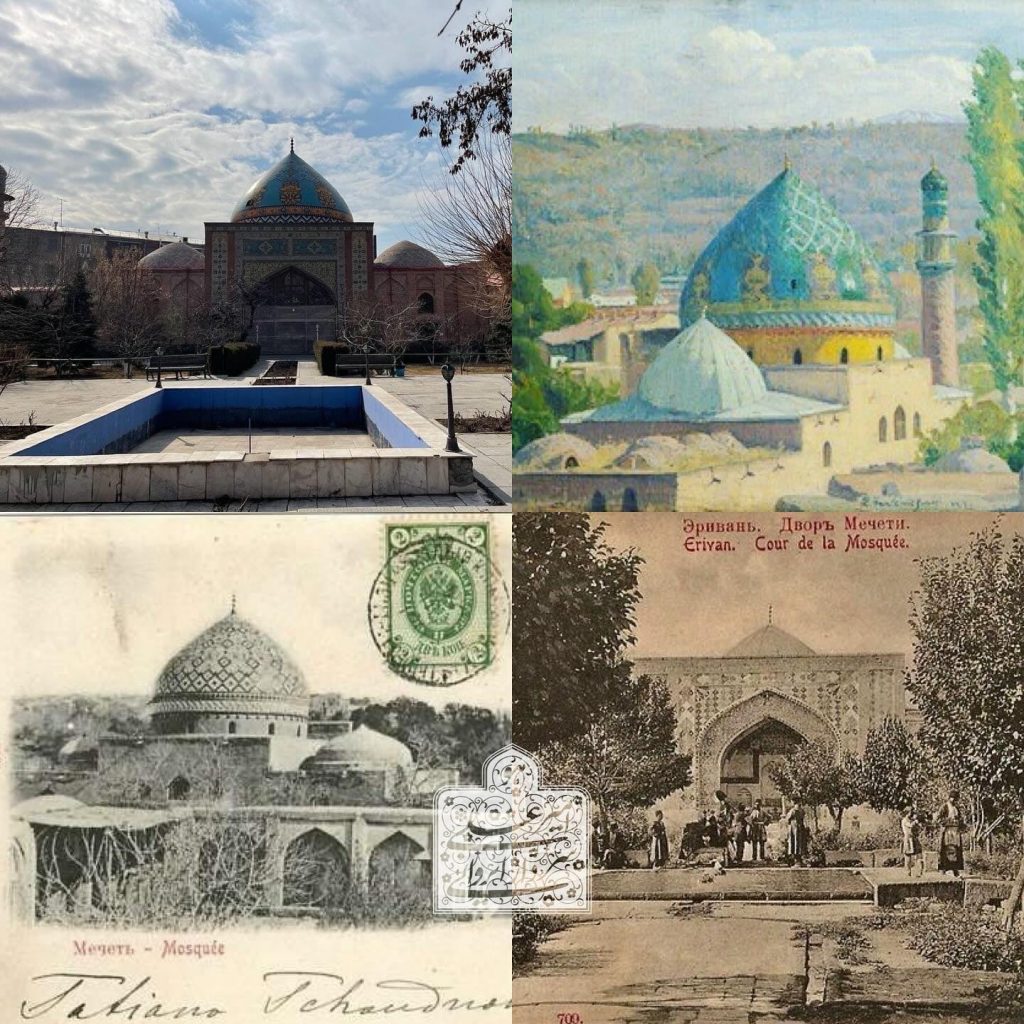

The Khanate’s architectural legacy included mosques, palaces, and public facilities such as baths and bazaars, which thrived during its period of independence. The Sardar Palace and its famous Mirror Hall, a marble-floored, intricately decorated space with a central fountain, symbolized the Khanate’s wealth and its rulers’ affinity for Islamic architecture. The Blue Mosque, commissioned by Husseinali Khan, remains the only surviving structure from the khanate’s peak and is a testament to the architectural sophistication of the period. In the aftermath of the Russo-Persian wars, Russian rule led to significant changes in Iravan. Russian authorities implemented new administrative systems and promoted Armenian settlement, which gradually transformed the city’s demographic and cultural landscape. The political compromises that shaped post-war Caucasus ultimately resulted in the ceding of Iravan to Armenia as part of the newly independent republics that emerged in the early 20th century. The Qajar dynasty’s portrayal of the Iravan Khanate has left a lasting influence on its historical narrative. Early Qajar historians, loyal to the Qajar court, documented events from a biased perspective, often describing the Iravan khans as unfaithful or weak. This portrayal stemmed from the khanate’s diplomatic maneuvering, which saw its leaders switching alliances between Iran, Russia, and the Ottomans in an attempt to retain their independence. The Qajar rulers felt threatened by the Iravan khans’ influence, leading them to promote a narrative that diminished the khanate’s autonomy and contributions. The Qajar conquerors depicted their takeover of Iravan as a necessary measure to restore their authority in the region, although this version often ignored the khanate’s achievements and unique political strategy.

After the final annexation by Russia, the erasure of Iravan’s khanate history continued. Russian authorities, and later Armenian nationalists, emphasized narratives that aligned with their own political agendas, often minimizing the contributions of the Turkic Iravan rulers. This erasure extended to the physical landscape, as many architectural relics of the khanate, including mosques and caravanserais, were systematically demolished or repurposed, erasing visible traces of the region’s past rulers. The Iravan Khanate’s legacy, however, persists in oral traditions, architectural records, and the descendants of its leaders. The family of Mahammad Khan Iravani, for instance, maintained a high standing in Qajar society, intermarrying with the Qajar royalty and assuming influential positions within the military and administration. This lineage continued to play a role in Iran history, even under the Pahlavi dynasty, although their historical significance was often overshadowed by new political narratives.

The decline of the Iravan Khanate serves as an example of how shifting power dynamics in the Caucasus repeatedly reshaped regional identities and allegiances. Iravan’s history reflects a complex interplay of diplomacy, cultural integration, and strategic adaptation that enabled the khanate to maintain autonomy amid powerful rivals. Yet, as with many contested regions, its legacy has been reframed by successive powers, from the Qajar dynasty to Russian and Armenian authorities. Today, the Iravan Khanate’s history represents a layered past, offering insights into the ways cultural, political, and military pressures shape historical memory.